13 June 2024 – Dr Sophie Louisa Bennett, PhD Conservation Biology (Lincoln 2016), MA Modern and Medieval Languages – German and Swedish (KC 1987, Cantab 2020), Diploma in Translation – German into English (City University/Institute of Linguists 1998)

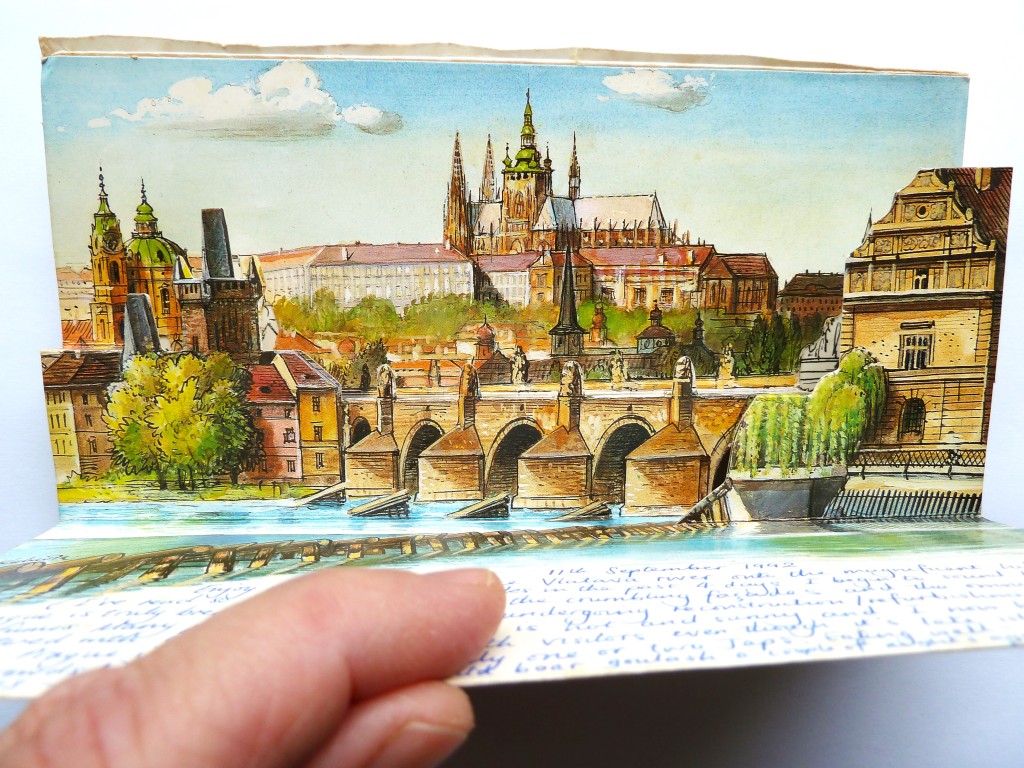

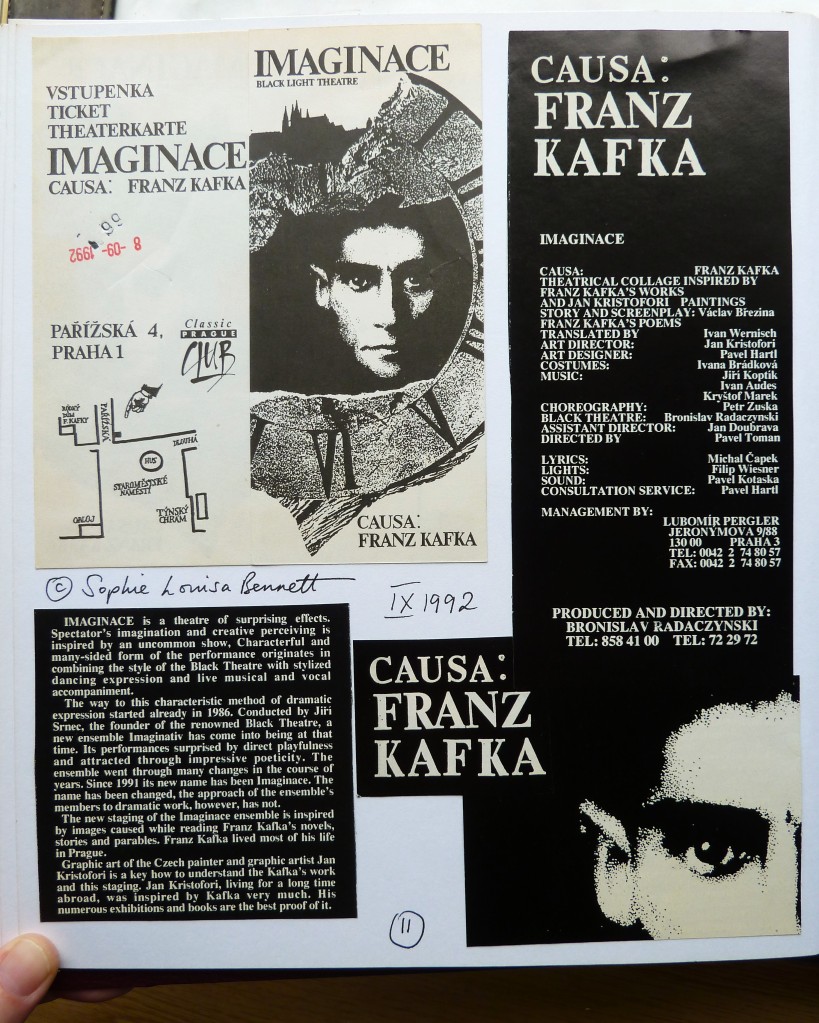

Franz Kafka was a novelist and story writer, and is considered to be one of the most important writers of the first half of the 20th century. He was born in Prague on 3rd July 1883 at a time when Prague and the Czech Republic/Czechia was part of the Austro-Hungarian, and died at Kierling (near Vienna) on 3rd June 1924. Kafka was the son of a middle-class, well-to-do Jewish businessman. As a young man and throughout his life, with the exception of the final few years, Kafka suffered poor mental health as a result of his sensitive and introverted nature; it is implied that this was the consequence of Kafka being the son of a father who was exclusively concerned with social advancement and commercial success. Kafka dealt with his issues in ,,Brief an den Vater” – Letter to my father (November 1919).

He attended the Prague-Altstadt Grammar School (Deutsches Gymnasium Prag-Altstadt) between 1893 and 1901 – successfully completing his schooling, contrary to his own perspective on this period. Interested in Ibsen and Naturalistic drama, Spinoza and Nietzsche, influenced by Darwin’s evolutionary theories and an avowed Socialist.

In his first two Semesters at university he switched between various subjects – appearing to remain undecided. Under August Sauer he studied Hebbel and Stifter. Then in accordance with his father’s wishes Jurisprudence/Law. Alongside which he participated enthusiastically, but rather passively, in Prague’s literary circles. He became influenced by readings of Brentano, Flaubert and Hoffmansthal. Somewhere around this time he struck up a friendship with Max Brod, who was to become his literary executor, posthumous editor and publisher. He took his law degree (for State certification) in the summer of 1903. In July 1905 a stay in the sanatorium at Zuckmantel (Schlesia) is noted, during which time he met a woman (thought to have inspired Hochzeitsvorbereitungen auf dem Lande – Preparations for a Country Wedding, 1906/07). Then between November 1905 and June 1906 he completed his doctoral exams and became Dr. jur. (Dr of Law). After receiving his doctorate he spent more time in the sanatorium at Zuckmantel. Autumn 1906 to autumn 1907 he undertook his articles or the practical element of his legal training, and was subsequently taken on – hopefully to the satisfaction of his father – by Assicurazioni Generali, an insurance firm.

On 30th July 1908 Kafka started work as an assistant officer at the Workers’ Accident Insurance Corporation[1] for the Kingdom of Bohemia (Arbeiter-Unfall-Versicherungsgesellschaft für das Königreich Böhmen) in Prague, where he quickly made a name for himself as an insurance lawyer. However he does not find the work fulfilling. He becomes increasingly withdrawn, from both his literary and social life and keeps company only with a small circle. Any dialogue becomes the monologue of his diary, which he wrote from 1910 onwards and in which he conducted his own merciless self-analyses, wrote down his dreams, outlines of work he intended to write, epigrams and his thoughts on whatever he read.

Holidays provided a break from the monotony and loneliness of his life: in 1909 he travelled to Italy with Max and Otto Brod (Aeroplane in Brescia – Taking Flight to Brescia), went to Paris in 1910, to Switzerland, Italy again and Paris with Max Brod in 1911 (Richard und Samuel, 1912), travelled to Leipzig in 1912 with Brod, where he became acquainted with the publisher Rowohlt and Wolff, and then on to Weimar in the footsteps of Goethe. In 1911 he started to study the Jewish (his) faith and Hebrew, in earnest it seems. Between August 1913 and 1917 he found himself in an unstable relationship with Felice Bauer from Berlin, to whom he was engaged twice. In the autumn of 1913 he met a young Swiss woman in the sanatorium Riva. From 1915 he lived in his own apartment in Prague.

Kafka interpreted the outbreak of tuberculosis in August 1917 as a sign that Destiny was working against his future plans, and, as a result, he parted from Felice Bauer for good. Prolonged stays in the country, first with his youngest sister Ottla in Zürau near Saaz, were interspersed with attempts to go back to work, which ultimately failed, with the result that Kafka went into early retirement. He intensified his engagement with the Jewish religious tradition, undertook light outdoor work, swum and went walking. From 1919 there ensued stays in various different sanitoriums. In the autumn of 1919 he got engaged for the third time, but this did not last long. In 1920 he met Milena Jesenska-Pollak in Meran (Briefe an Milena – Letters to Milena, 1952). Mental and physical pain. Renewed reading of Kierkegaard and an existential struggle with his Jewish faith. In 1921 he made the acquaintance of Robert Klopstock who would later, as a friend, supervise him medically in the final stages of his suffering.

There was however a decisive change for the better in Kafka’s life story when he met Dora Dymant, the 20-year-old of Polish-Hassidic descent, on the Baltic coast in the summer of 1923. At the end of July 1923 he moved to Berlin, breaking away from Prague and his parents. Despite both material hardship and poor physical health he experienced relatively happy months with his companion by his side, and a phase of quiet productivity. But he was nonetheless dogged by illness. In March 1924 Brod was the one who brought the ailing Kafka – at this stage terminally ill – back to Prague, which the latter saw as a final triumph of his father’s will over him and over his life. He was defeated. He spent his final days in the sanatorium in Kierling near Vienna, where he was barely able to eat due to tuberculosis [Kehlkopf– indicates larynx – so was this a form of cancer rather than TB?] and was only able to communicate with Klopstock and Dora Dymant in written form. On his final day on earth he set about correcting the volume Der Hungerkünstler – The Starving Artist (1921 – 1924). Kafka died on 3rd June 1924. He was laid to rest in the Jewish cemetery Prague-Strašnice on 11th June 1924.

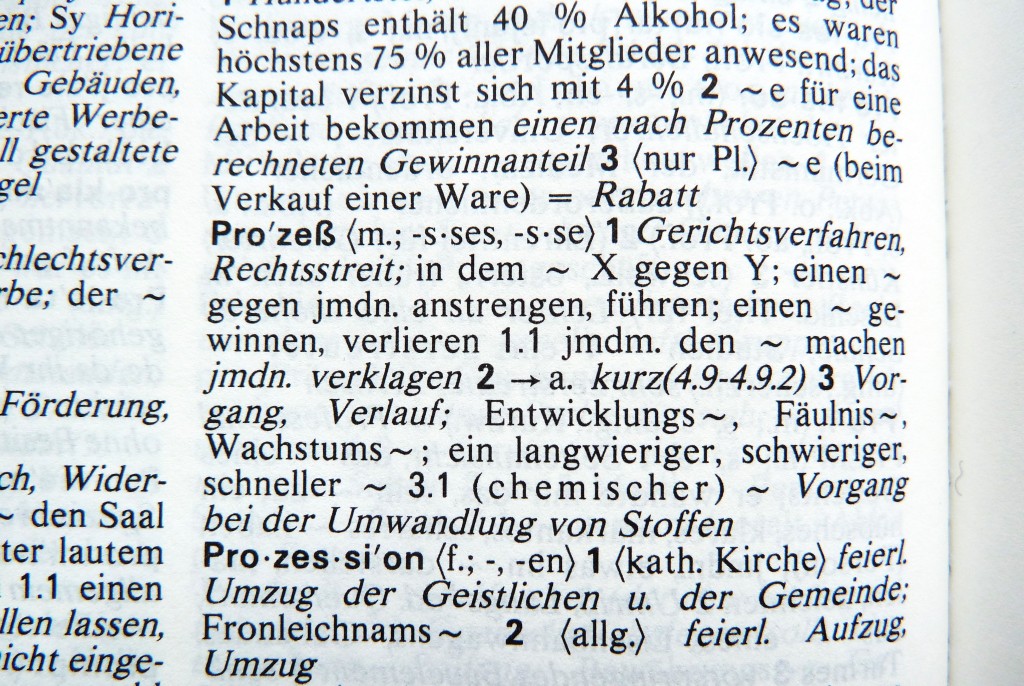

During his lifetime Kafka published only a limited number of his works: 6 publications in book form, plus a few contributions to magazines. The majority of his writings were published by Max Brod, against his express wishes which were to destroy anything unpublished. The editions Brod produced are not without their faults (,,nicht einwandfrei” – what is I ask myself?), since Kafka left no instructions on how the work was to be organised. This issue has even preoccupied researchers, who have discussed the possible arrangement, organisation and order of the chapters of Kafka’s novels.

Source of biographical material:

Kunisch, H. (1965) Handbuch der deutschen Gegenwartsliteratur [Handbook of Contemporary German Literature]. München: Nymphenburger Verlagshandlung [Published ,,unter Mitwirkung von Hans Hennecke” – in collaboration with Hans Hennecke]. The section on Kafka: 325-329. This book was acquired as surplus stock from the Institute of Germanic Studies while I was a library assistant/SCONUL trainee between 1991 and 1992.

[1] Gesellschaft can be translated directly in the sense of ‘a [cooperative] society’, in the context of corporate bodies, but I have chosen a different word. ‘Company’ is also frequently used – as in a business entity.

Titles of some of Kafka’s works may not be what you are anticipating – e.g. Hungerkünstler is evidently more commonly translated as “The Hunger Artist”.

Dr Sophie Louisa Bennett