6 May 2024 – Dr Sophie Louisa Bennett, PhD Conservation Biology (Lincoln 2016), MA Modern & Medieval Languages – German & Swedish (KC 1987, Cantab 2020), Diploma in Translation – German into English (City University/Institute of Linguists 1998)

It’s a sunny Bank Holiday and the May is still in bloom and has been for some days. By ‘the May’ I mean Hawthorn (Crataegus species), a common hedgerow plant, abundant in farmland hedges. Or at least once upon a time.

There are a number of reasons I think of ‘the May’ at this time of year – how I’d taken a picture of Karin T. during our last term at King’s, smiling beneath a May Tree in the evening glow, either on the way to Grantchester or along a pathway beyond Robinson (strangely enough), how it meant a lot to me during fieldwork for my PhD, and how ‘May’ may now well become a misnomer, since the flowering season has extended backwards into April. Just like May Balls are in June…

Even at the time John Clare (1793 – 1864) wrote his Sonnet (one of a number – see below) April appears to have been the start of the flowering season. Some may say that this woody plant, though magnificent, smells not nearly as lovely as it looks. And there are thorns too, to catch you out. Although not nearly as nasty as the Blackthorn.

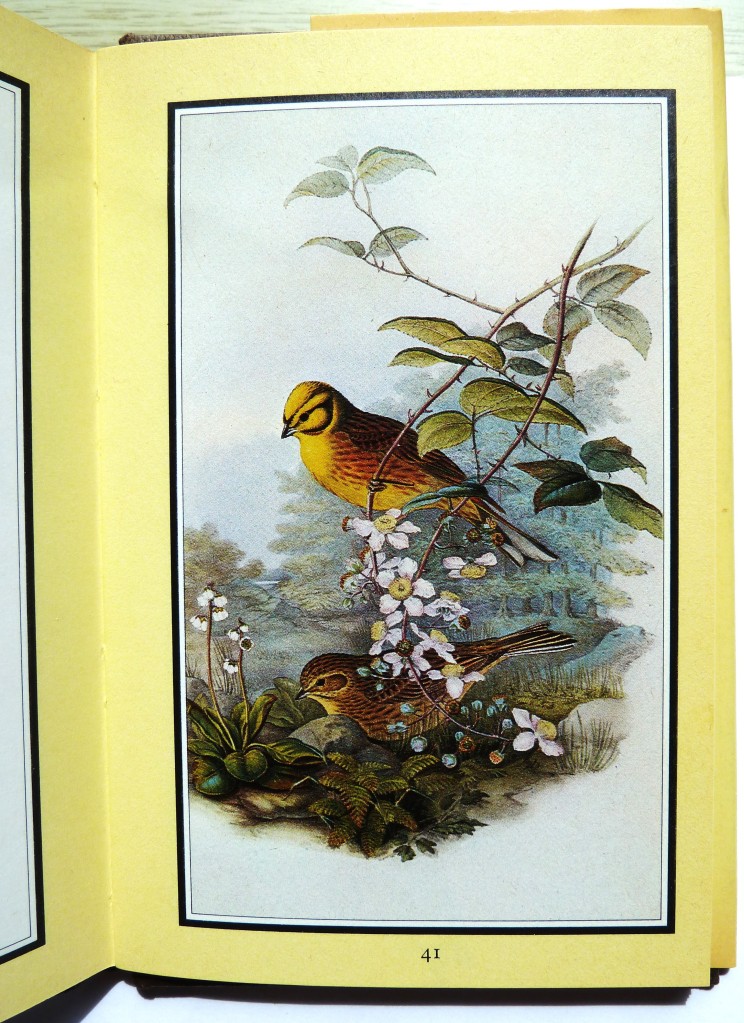

Besides this sonnet, the (H)awthorn or white thorn is referred to in a number of Clare’s poems including The Yellowhammer, a poem which I used as both inspiration and a header for an undergraduate essay on the conservation of farmland birds during my BSc in Conservation Biology.

Sonnet

How beautiful the white thorn[1] shews its leaves

The first in springs beginnings march or close

Of April and how very green it weaves

The branches in the underwood they burst

More green than grass the common eye receives

Pleasures o’er green white thorn clumps in the wood

So beautifully green it seems at first

It does the eye that gazes on it good

The green enthusaism [sic] of young spring

The Blackbird chooses it from all the wood

With moss to build his early nest and sing

Among the leaves the young are snugly nurst

Mornings young dew wets each pinfeathered wing

Before a bunch of May was from its white knobs burst.

Notes:

[1] White thorn is another name for Hawthorn. The edition I have includes a glossary, but that glossary omits ‘white thorn’ as a term and makes no cross-reference to ‘awthorn’ as Clare also liked to refer to it. Presumably since the editors reasoned that such a common hedgerow plant would not require further explanation.

Source of text of ‘Sonnet’:

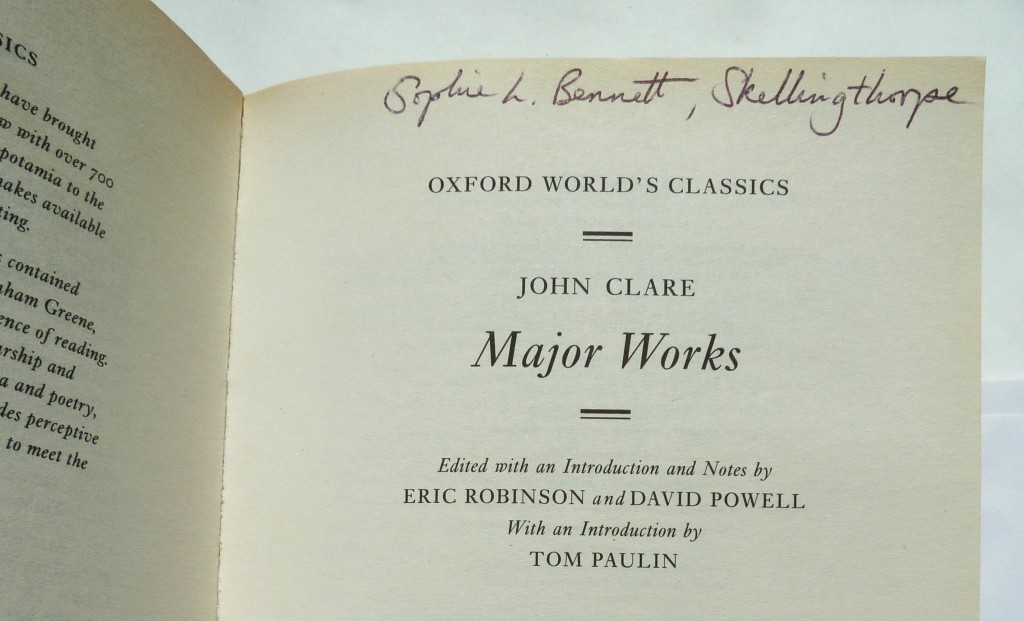

Robinson, E. and Powell, D. [Eds.] (2004) John Clare: Major Works – including selections from The Shepherd’s Calendar. Oxford: OUP – Oxford World’s Classics [With an Introduction by Tom Paulin]. ISBN: 978-0-19-954979-5. This edition first published in 1984 with the Introduction by Tom Paulin added in 2004 and then reissued in 2008]. The edition includes a tribute to librarians and archivists by the editors.

Biographical notes [from the preface and back cover of the Oxford World’s Classics edition]:

John Clare (1793 – 1864) is now recognized as one of the greatest English Romantic poets, after years of indifference and neglect. Clare was an impoverished agricultural labourer – rising to fame as the Northamptonshire Peasant Poet in 1820 with the publication of his Poems Descriptive of Rural Life and Scenery. Despite the success of this work and the subsequent publication of three more volumes of verse his genius was not generally appreciated by his contemporaries. He fell into want and neglect, and his later mental instability further contributed to his loss of critical esteem. Suffering from mental illness he entered an asylum in Epping Forest as a voluntary patient. Four years later he walked away from this place to his home at Northborough, but in 1841 he was committed to Northampton General Lunatic Asylum. Where he died.

Throughout most of his life, he wrote voluminously – remarkable observations of the natural life of the Soke of Peterborough, love songs and lyrical poems of the greatest delicacy, ribald satire and ballads and is considered to be one of the earliest and best recorders of English folk traditions.

The extraordinary range of his poetical gifts has more recently restored him to the company of his contemporaries Byron, Keats and Shelley, and this fine selection [the Oxford World Classics edition’s own words] illustrates all aspects of his talent. It contains poems of all aspects from his body of work, including love poetry, and bird and nature poems. Clare’s work provides a fascinating reflection of rural society, often underscored by his own sense of isolation and despair.

The cover illustration for the book is from Harvesters Resting by Peter de Wint (1784 – 1849), Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. [A combined effort therefore!]

The Yellowhammer

When shall I see the white thorn leaves agen

And Yellowhammers gath’ring the dry bents

By the Dyke side on stilly moor or fen

Feathered wi love and natures good intents

Rude is the nest this Architect invents

Rural the place wi cart ruts by dyke side

Dead grass, horse hair and downy headed bents

Tied to dead thistles she doth well provide

Close to a hill o’ ants where cowslips bloom

And shed o’er meadows far their sweet perfume

In early Spring when winds blow chilly cold

The yellow hammer trailing grass will come

To fix a place and choose an early home

With yellow breast and head of solid gold.

We used to get Yellowhammers in the garden – the vivid males and the slightly less vivid females would visit to feed. Not for some years now though. I hear them but do not know where they are. Perhaps somewhere in the fields beside the cycle path. Minding their business and lying low. For me this used to be the sound of summer too, the call of the Yellowhammer: Little-Bit-of-Bread-and-No-Cheese – one of the first bird calls you would learn to identify as a child because it is so distinctive. (Unlikely now that you would find no cheese in our household and probably at one time or another we have also fed some to the birds when in need.)

Considering both Clare’s Sonnet and The Yellowhammer it is possible to sense both the joy and melancholy in his voice. Nature is regarded as being ‘healing’ but for him this became problematic. His head was evidently full of the images of the natural world and its workings he saw about him. And as an agricultural labourer, while he appears to have had a good education (eccentricities in spelling can be excused on the basis there was not the same standardisation as we now see in written English), he did not have the luxury of becoming a poet full time and evidently his few volumes did not make him sufficient money to keep afloat. We see this so often with creative people – and often poets and writers in general – that they are tormented by something that they try to put a name to. And this is likely to be one of the reasons, alongside a humble background, that John Clare ‘defied’ – and reviled – any standardisations in grammar and spelling.