11 June 2024 – Dr Sophie Louisa Bennett, PhD Conservation Biology (Lincoln 2016), MA Modern and Medieval Languages – German and Swedish (KC 1987, Cantab 2020), Diploma in Translation – German into English (City University/Institute of Linguists 1998)

Who knows why these things pop into your head [I had no idea it was the 100th anniversary of Kafka being laid to rest in the Prague-Strašnice Cemetery]. Although there has been an awful lot of footage of people going to court and sitting in court and coming out of courts on the TV in the last few years. An increasing amount of time given is over to this, in fact. Are we more badly behaved than ever before? Certainly seems so. ‘We’ also have the apparatus with which to prosecute this behaviour, the means and the time. And while thinking about this and thinking back to a time when I might even have considered doing law conversion, I also think back to King’s and another student of German – quite an outstanding one – who subsequently chose to ‘pursue’ the Law…

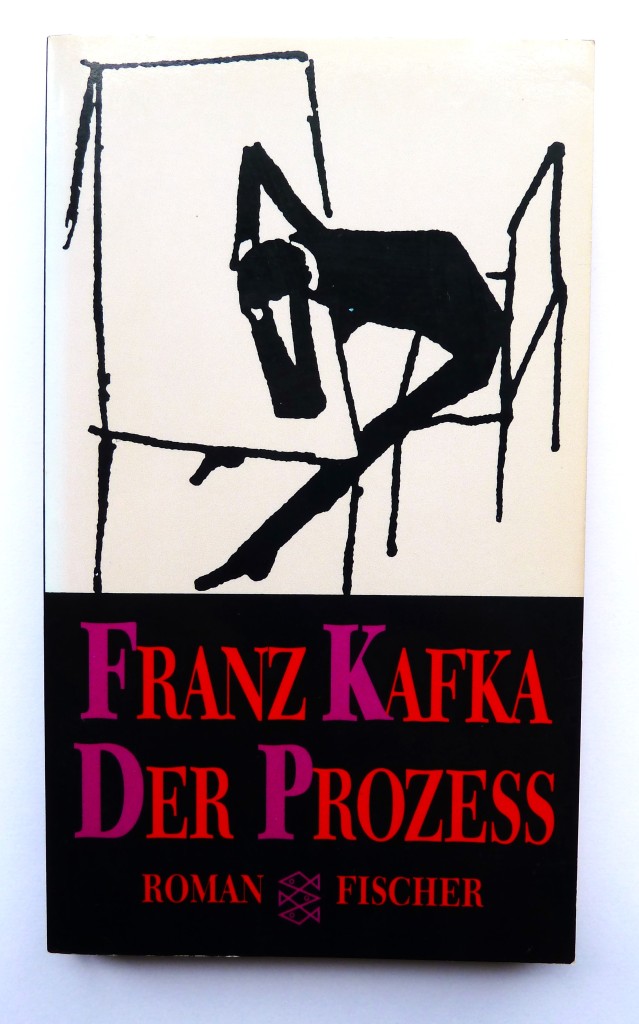

Probably lesser known than Franz Kafka‘s (1883 – 1924) Die Verwandlung (you know, the one about a ‘transformation’ in which he/the protagonist ‘turns into a beetle’ and flails about on his back), Der Prozeß (The Trial) is not necessarily as it seems at first from the title. While it does deal with the ‘Byzantine’ nature of bureaucracy and the legal system (both of which Kafka was familiar with from his working life), it is really about his internal life and his own feelings of being persecuted, for no apparent reason, self-doubt and self-consciousness. In effect, he is putting himself on trial. And feeling judged. You might even use that utterly distasteful and so widely- and carelessly-used term ‘paranoia’ in this context.

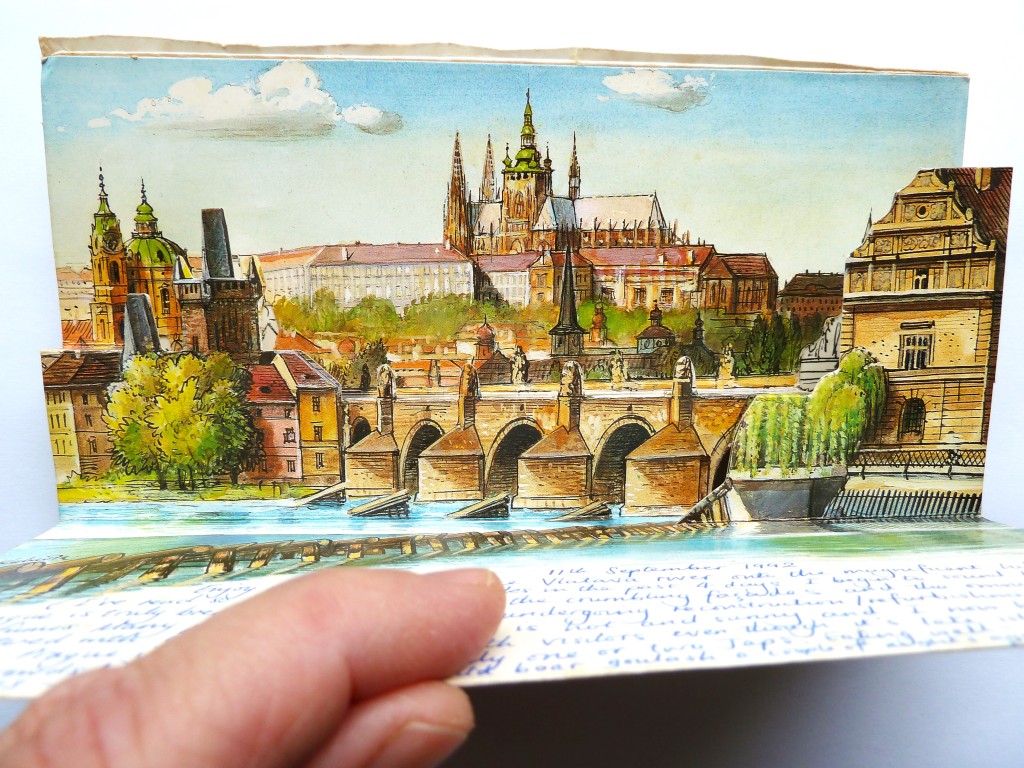

At times Kafka evidently felt as if he was hanging on by his fingernails. As if he had been defenestrated – thrown from a window in the Hřad perhaps. Yes, no coincidence that Das Schloss (The Castle) featured as one of his titles, given he was born in Prague into the German-speaking Jewish community and drew his inspirations from his seemingly limited life there.

Illustrations: V. Kubašta (whose signature is on the reproduction of the watercolour) & R. Kubašta & GPS, 1992. Contact: Prague 5, Vltavská 2, Czechoslovakia. Photo: Sophie Louisa Bennett with Panasonic Lumix

***

When Der Prozeß was published in 1925 by Max Brod, a year after Kafka’s death, the latter’s name and reputation as an author was still unknown to most and familiar only to a small circle. Ten years later such was Kafka’s posthumous reputation that a volume of his collected works was brought out. Today, Kafka’s novels and short stories have taken their place alongside other works considered to be ‘world literature’. The influence of his work on contemporary writing, the influence of his novels, in particular Das Schloss (The Castle) and Der Prozeß (The Trial), cannot be denied. [Or at least that is what Fischer Tashenbuch Verlag believes.] “What were originally only private scribblings, with express instructions that they were NOT for publication became an expression of metaphysical despair, representative of the mood of the times in which he lived“, wrote Walther Killy with regard to Der Prozeß.

“The trial which is the theme of this novel is the eternal process in which a sensitive person is engaged in a struggle with their own conscience. Protagonist K. stands before his internal accusers, judge and jury and executioners. The ghostly proceedings are conducted in the most unlikely and seemingly inconspicuous of places – as show trials effectively [hence Brod’s use of the word ,,Schauplätze”] – and in such a way that K. ultimately always appears to be in the right. (And yet is judged because he behaves often as if he is guilty – then repeatedly has to justify himself.) In the way that we are always judgmental towards ourselves and try to quell our persistently bad conscience, brush our fears aside and make light of them. [Although in Kafka’s writing this is not a light-hearted ‘refrain’ or trivial Bagatelle – it is serious and nightmarish]. What marks this writing out is Kafka’s instinctive understanding of psychology and feeling for the inner voice, which becomes ever louder and clearer to the reader.” Max Brod.

Brod was the one who went through his friend and fellow writer Franz Kafka’s papers when he died. He observed that it was a pity that Kafka had been acting as his own executor even before he passed away finally: Kafka had destroyed many papers, leaving the covers only as a legacy. He had also burnt numerous writing pads. What remained were around a hundred aphorisms relating to religious questions, an attempt at an autobiography (when clearly many of his works can be seen in that light), and a pile of unsorted pieces of paper. For Brod sorting through what Kafka had left behind must have been something of a torment. He hoped that he would find publishable material – completed stories, or at least something he had managed to finish. Brod was given in addition an incomplete novella and a sketch book. Some items had been removed from Kafka before he had a chance to destroy them: three novels, including Amerika, which was in the possession of a female friend. The other two, Das Schloss and Der Prozeß, had already been presented to Brod in 1920 and 1923 respectively – which Brod called a “consolation” (Trost), something you would say if you had stuck with someone for years tolerating their eccentricities and behaviour and felt that this was some compensation, especially since you (i.e. Brod) were not only a writer but also an editor/publisher. He was especially disappointed that he could not find the works that Kafka had at some point read aloud to him or told him about in outline: they were nowhere to be found in his apartment. He vowed to honour his dead friend by retrieving as much as he could for publication. Kafka had not even given the novel now known as Der Prozeß a title – he had however often referred to that work using that name, in conversations with Brod. Whether he was referring ironically to the trials and tribulations of writing is not spelled out but could be surmised. Kafka had given titles to chapters and put them in some sort of order, but the rest was up to Brod (as is the role of an editor). And because he had heard a large part of the novel read aloud he had some ‘feeling’ for how Kafka’s papers should be arranged. Kafka had implied that the reason Der Prozeß ultimately remained unfinished was that he felt this was a process which could not end and went on into infinity. He seemed to have been grappling with a philosophical dilemma which many a philosopher from the ancients up to modern times has grappled with: the cyclical, repetitious nature of reality. The form and the content were not necessarily designed to express this but arose organically from his writing process and are a clear reflection of his difficulty in completing the novel and coming to any conclusions.

These are translated from the additional materials in my 1989 edition of Kafka’s novel, plus my own thoughts on the matter. Dr Sophie Louisa Bennett (Lincoln 2016), MA (KC 1987, Cantab), Diploma in Translation (City University/IoL 1998).

***

I have to admit, while you might identify with many of his frustrations and emotions, you can also feel as if you are going mad when reading Kafka. Sisyphean is how you might describe this – his themes, his process, the required reading effort. Even if his works belong to the canon of world literature, he is still a very hard read at times and not one easily ticked off your list – you have to MAKE yourself read Kafka, unless in an academic context. And no wonder one of my former Cambridge lecturers, Michael Minden, once declared that sanity may even be merely a more common form of insanity! Although I think that might well have been with reference to Büchner (I suspect Wozzeck) rather than Kafka, since I kept a quote from him from my first year and I only studied literature of the 19th century for Part I in German.

Despite my fascination with Kafka’s internal struggles I did not do as well as I might on the 20th century German paper during University Finals in 1991, and remained fundamentally a 19th-century-kind-of-girl. (And, yes, we did read all of our set texts in the original language and not only in translation!)

My edition: Kafka, F. (1989) Der Prozeß [The Trial/The Process]. Frankfurt am Main: Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag. ISBN: 3-596-20676-6

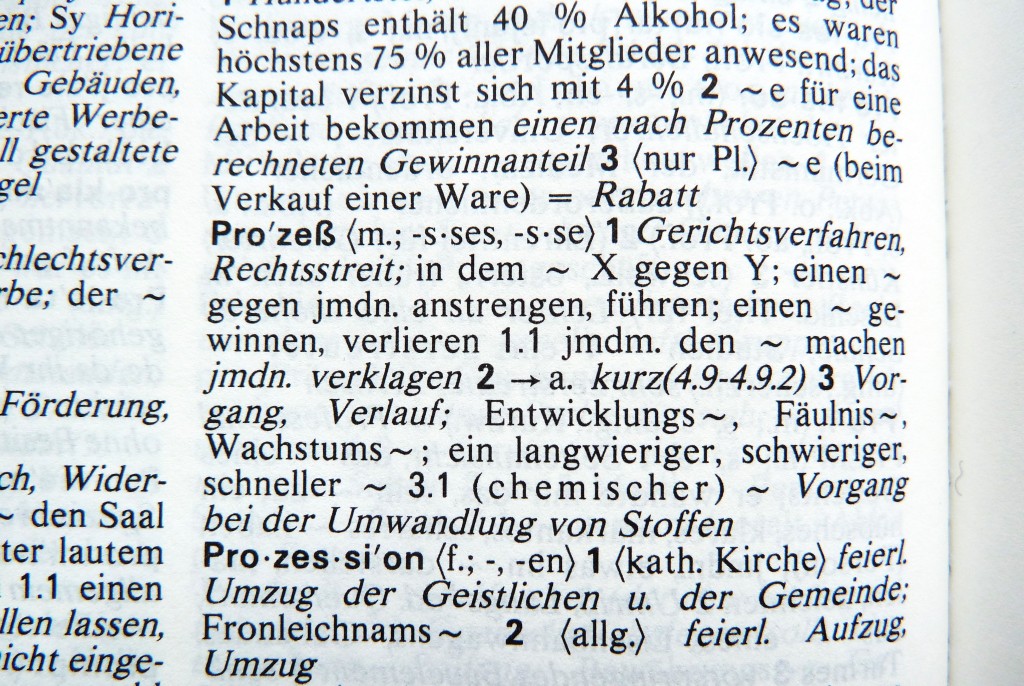

Note on the word ‘Prozeß’: It will perhaps be self-evident to even an English-speaker, but the use of Der Prozeß as the title by Franz Kafka is also an expression of the novel’s duality, or even triality. The word can be translated as a process, in terms of a (bio-)chemical process perhaps or in other non-legal contexts, but is also associated with the Law and the Courts. In my trusty Wahrig (1986 imprint of a 1978 edition), Entwicklungs– (developmental), Fäulnis– (rotting, decomposition), Wachstums– (growth) processes are all indicated. All processes to be found in Kafka’s writing. There are also processes which are long-winded, difficult, or even, if you are lucky, quick. But this may depend on your reading ability in German, including the length of time since you last picked up a German language book.