Subscribe to continue reading

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

Fachübersetzung Deutsch-Englisch : Nachhaltigkeit, Bio- und Naturwissenschaften

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

8 May 2024 – Dr Sophie Louisa Bennett, PhD Conservation Biology (Lincoln 2016)

Orang-(h)utans (People of the Forest) are often considered to be closer to being ‘human’ than most other apes, and it is perhaps for that reason that they pull on heart strings more than other species. They seem slower and less aggressive, more trusting, than other apes. They have a similar lifespan to humans, are not sexually mature until they hit their teens – therefore have to survive in diminishing circumstances for a dangerously long period before reproducing – and generally do not have more than one baby, rarely two – their ‘replacement’ rate is therefore low.

Hard to imagine now, but the dividing line between apes and the category ‘homo‘ (a group embracing human species) taxed 17th century anatomists and taxonomists to the extent that Linnaeus, the ‘Father of the Binomial’, when he devised his scheme for classifying all life-forms in the 1730s, opted to class apes and humans in different genera, but only after considerable thought and changing his mind. The question was not settled until the early 19th century when scientists finally determined against the human credentials of the last ape to qualify for consideration, the orang-utan. In fact, doubts regarding the categorisation of some human tribes are said to have persisted at least as long (i.e. if not longer) than doubts regarding the orang-utan (Fernández-Armesto, 2015).

FFI, an organisation I have supported for a number of years, periodically updates members on its projects and successes. In the case of the orang-utan, FFI helped secure the protected status of the Bukit Batikap forest in Central Kalimantan, which provides a safe environment in which to release rehabilitated orang-utans. FFI also helps fund ongoing orang-utan protection work in the forest, including training for forest rangers.

If you can’t get to Kalimantan you can however see orang-utans elsewhere… including Monkey World in Dorset. They are one of the chief attractions of the place – and were certainly a motivating factor for Mum when we visited Dorset in 2016. After many years of watching the Cronins on TV, I think she finally fulfilled a long-held ambition to see Oshine and others. They were an endearing sight.

Orang-utans cannot survive independently until around six years old, so orphaned babies have little hope of survival if they are left to fend for themselves. Also, many babies are captured to supply the illegal pet trade – with the mothers usually being killed in the process. FFI works with and supports local organisations that rescue and rehabilitate orphaned and pet orang-utans, preparing them for their eventual return to the wild.

Orang-utans (like many other species abandoned when very young and imprinted on human carers) do not possess innate survival skills, so rehabilitation workers teach orphaned babies how to do things like climb trees and forage for food. FFI works with partner organisations to safeguard orang-utan habitats and to facilitate the release of rehabilitated orang-utans into the wild.

In my opinion, idealistic as it is, the best way to ensure their future – and that of other non-human species – is to preserve and protect as much of their habitat as possible. In preserving their forest environment, FFI is helping to enable the ‘people of the forest’ to live as freely as they can in – and despite – our presence.

Reference:

Fernández-Armesto, F. (2015) A Foot in the River: Why Our Lives Change – and the Limits of Evolution. Oxford: OUP. ISBN: 978-0-19-874442-9

6 May 2024 – Dr Sophie Louisa Bennett – PhD Conservation Biology (Lincoln 2016), MA Modern & Medieval Languages – German and Swedish (KC 1987, Cantab 2020), Diploma in Translation – German into English (City University/Institute of Linguists 1998)

I got a message from the (near-) present and a reminder of the distant-ish past when a lovely post card arrived for me in the past few days. A reproduction of an old transport poster – one of my favourite types of art.

The card reminded me of a trip down the Thames to the Flood Barrier with a friend on an old paddle steamship which hailed from ‘up north’. The P. S. Waverley.

I do believe we two – Jan and I – even waved from the Waverley. And I, at least, also sent a message or two…

I can’t rightly recall who suggested this river cruise – maybe one of the engineers at work who had some marine knowledge and/or was working on an A&D project at the time. Mostly I’d been looking at aircraft, but a boot would do. And I probably have a better head for sea level than anything higher up. Not to overlook the webbed hands and feet.

I don’t swim well, but, I reasoned, there would be life savers and rings. And Jan, I knew, had both Scottish affiliations and loved water sports, so perhaps she would like to come along too.

I duely sent a cheque for the required amount and received paper tickets and a message from one of the organisers. I can’t remember if we did introduce ourselves – maybe as we boarded at the Pier. There was no intention of finding anyone in a uniform, even if this had been organised by The Royal Institution of Naval Architects.

There we were, the two of us, youngish, free and single, ganning – or rather steaming – down the Thames on the P.S. Waverley, from the Pier, via Tower Bridge all the way down to the Thames Flood Barrier – and back ‘up’ again.

There were images of Jan and I posing on board, of Tower Bridge, of the City, of the Flood Barrier itself and possibly also the workings of the engines below deck, but these, as with many photos, may have been misplaced over time. I find that a lot of things have gone missing and that there are copies of items which are evidently not the originals, when I knew very well I had the originals in the albums… because in many cases the hard copies had a Mayfair photo developer’s mark on the reverse, since they were round the corner from work from Berger.

And that was my only – and therefore longest – river cruise on the Thames – all others had been made by public transport links (to/from Westminster Pier, not Tower Pier) – with family and friends.

P. S. Waverley, I loved you!

6 May 2024 – Dr Sophie Louisa Bennett, PhD Conservation Biology (Lincoln 2016), MA Modern & Medieval Languages – German & Swedish (KC 1987, Cantab 2020), Diploma in Translation – German into English (City University/Institute of Linguists 1998)

It’s a sunny Bank Holiday and the May is still in bloom and has been for some days. By ‘the May’ I mean Hawthorn (Crataegus species), a common hedgerow plant, abundant in farmland hedges. Or at least once upon a time.

There are a number of reasons I think of ‘the May’ at this time of year – how I’d taken a picture of Karin T. during our last term at King’s, smiling beneath a May Tree in the evening glow, either on the way to Grantchester or along a pathway beyond Robinson (strangely enough), how it meant a lot to me during fieldwork for my PhD, and how ‘May’ may now well become a misnomer, since the flowering season has extended backwards into April. Just like May Balls are in June…

Even at the time John Clare (1793 – 1864) wrote his Sonnet (one of a number – see below) April appears to have been the start of the flowering season. Some may say that this woody plant, though magnificent, smells not nearly as lovely as it looks. And there are thorns too, to catch you out. Although not nearly as nasty as the Blackthorn.

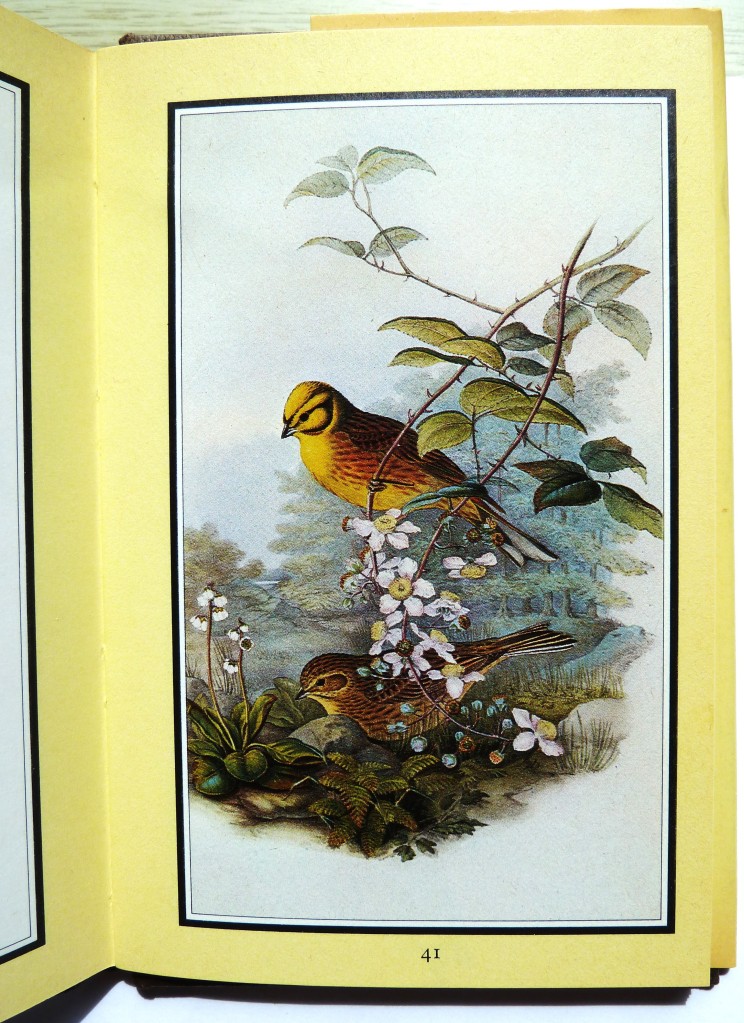

Besides this sonnet, the (H)awthorn or white thorn is referred to in a number of Clare’s poems including The Yellowhammer, a poem which I used as both inspiration and a header for an undergraduate essay on the conservation of farmland birds during my BSc in Conservation Biology.

Sonnet

How beautiful the white thorn[1] shews its leaves

The first in springs beginnings march or close

Of April and how very green it weaves

The branches in the underwood they burst

More green than grass the common eye receives

Pleasures o’er green white thorn clumps in the wood

So beautifully green it seems at first

It does the eye that gazes on it good

The green enthusaism [sic] of young spring

The Blackbird chooses it from all the wood

With moss to build his early nest and sing

Among the leaves the young are snugly nurst

Mornings young dew wets each pinfeathered wing

Before a bunch of May was from its white knobs burst.

Notes:

[1] White thorn is another name for Hawthorn. The edition I have includes a glossary, but that glossary omits ‘white thorn’ as a term and makes no cross-reference to ‘awthorn’ as Clare also liked to refer to it. Presumably since the editors reasoned that such a common hedgerow plant would not require further explanation.

Source of text of ‘Sonnet’:

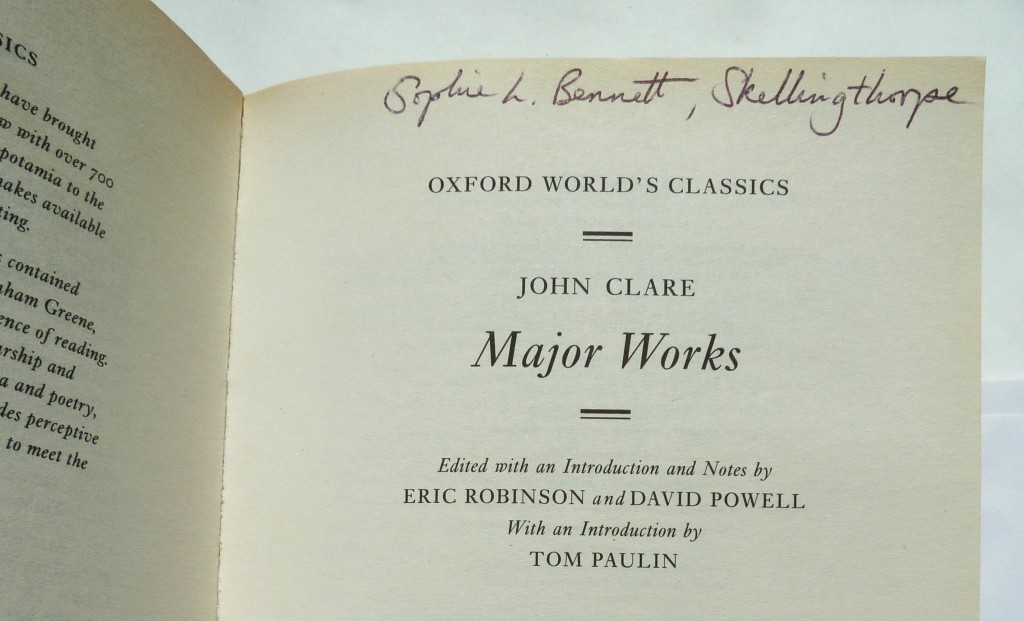

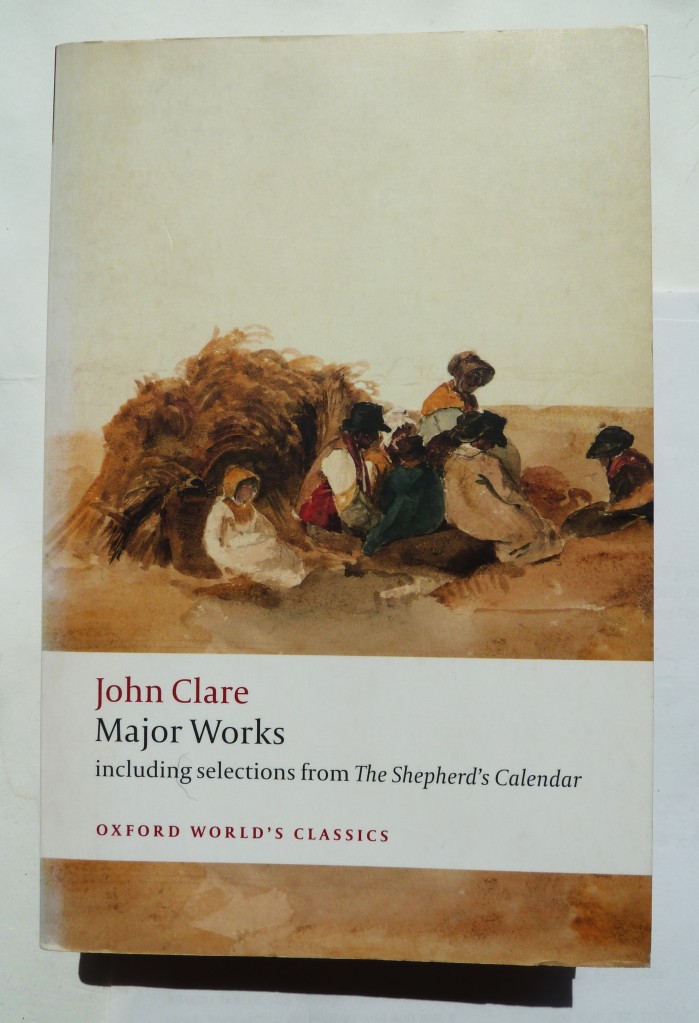

Robinson, E. and Powell, D. [Eds.] (2004) John Clare: Major Works – including selections from The Shepherd’s Calendar. Oxford: OUP – Oxford World’s Classics [With an Introduction by Tom Paulin]. ISBN: 978-0-19-954979-5. This edition first published in 1984 with the Introduction by Tom Paulin added in 2004 and then reissued in 2008]. The edition includes a tribute to librarians and archivists by the editors.

Biographical notes [from the preface and back cover of the Oxford World’s Classics edition]:

John Clare (1793 – 1864) is now recognized as one of the greatest English Romantic poets, after years of indifference and neglect. Clare was an impoverished agricultural labourer – rising to fame as the Northamptonshire Peasant Poet in 1820 with the publication of his Poems Descriptive of Rural Life and Scenery. Despite the success of this work and the subsequent publication of three more volumes of verse his genius was not generally appreciated by his contemporaries. He fell into want and neglect, and his later mental instability further contributed to his loss of critical esteem. Suffering from mental illness he entered an asylum in Epping Forest as a voluntary patient. Four years later he walked away from this place to his home at Northborough, but in 1841 he was committed to Northampton General Lunatic Asylum. Where he died.

Throughout most of his life, he wrote voluminously – remarkable observations of the natural life of the Soke of Peterborough, love songs and lyrical poems of the greatest delicacy, ribald satire and ballads and is considered to be one of the earliest and best recorders of English folk traditions.

The extraordinary range of his poetical gifts has more recently restored him to the company of his contemporaries Byron, Keats and Shelley, and this fine selection [the Oxford World Classics edition’s own words] illustrates all aspects of his talent. It contains poems of all aspects from his body of work, including love poetry, and bird and nature poems. Clare’s work provides a fascinating reflection of rural society, often underscored by his own sense of isolation and despair.

The cover illustration for the book is from Harvesters Resting by Peter de Wint (1784 – 1849), Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. [A combined effort therefore!]

The Yellowhammer

When shall I see the white thorn leaves agen

And Yellowhammers gath’ring the dry bents

By the Dyke side on stilly moor or fen

Feathered wi love and natures good intents

Rude is the nest this Architect invents

Rural the place wi cart ruts by dyke side

Dead grass, horse hair and downy headed bents

Tied to dead thistles she doth well provide

Close to a hill o’ ants where cowslips bloom

And shed o’er meadows far their sweet perfume

In early Spring when winds blow chilly cold

The yellow hammer trailing grass will come

To fix a place and choose an early home

With yellow breast and head of solid gold.

We used to get Yellowhammers in the garden – the vivid males and the slightly less vivid females would visit to feed. Not for some years now though. I hear them but do not know where they are. Perhaps somewhere in the fields beside the cycle path. Minding their business and lying low. For me this used to be the sound of summer too, the call of the Yellowhammer: Little-Bit-of-Bread-and-No-Cheese – one of the first bird calls you would learn to identify as a child because it is so distinctive. (Unlikely now that you would find no cheese in our household and probably at one time or another we have also fed some to the birds when in need.)

Considering both Clare’s Sonnet and The Yellowhammer it is possible to sense both the joy and melancholy in his voice. Nature is regarded as being ‘healing’ but for him this became problematic. His head was evidently full of the images of the natural world and its workings he saw about him. And as an agricultural labourer, while he appears to have had a good education (eccentricities in spelling can be excused on the basis there was not the same standardisation as we now see in written English), he did not have the luxury of becoming a poet full time and evidently his few volumes did not make him sufficient money to keep afloat. We see this so often with creative people – and often poets and writers in general – that they are tormented by something that they try to put a name to. And this is likely to be one of the reasons, alongside a humble background, that John Clare ‘defied’ – and reviled – any standardisations in grammar and spelling.

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

3 May 2024 – Dr Sophie Louisa Bennett, PhD Conservation Biology (Lincoln 2016), MA Modern & Medieval Languages – German and Swedish (KC 1987, Cantab 2020), Diploma in Translation – German into English (City University/Institute of Linguists 1998)

New research shows that parrots prefer to Zoom/FaceTime [OR OTHER SOCIAL MEDIA PLATFORM] – i.e. see them beak-to-beak, if not in the feather – their parroty friends rather than merely hear their voices? Who knew that such vividly-plumed birds were such visual creatures? And perhaps it helps them hear better…

It appears that the Soviets, however, knew this long ago.

My first question is: Why does it take research at a Higher Education institution to tell us so? Just get them a mirror instead. Perhaps a 1984-type ‘mirror’?

My second question is: Do parrots have accents and did these ones speak Glaswegian? Maybe that would account for some of their social behaviours.

I don’t have a third question…

3 May 2024 – Dr Sophie Louisa Bennett, PhD Conservation Biology (Lincoln 2016), MA Modern & Medieval Languages – German and Swedish (KC 1987, Cantab 2020), Diploma in Translation – German into English (City University/Institute of Linguists 1998)

Good news for anyone ever called ‘pinheaded’

Ever had anyone – in a jokey fashion or not – refer to you as having a small head or being ‘pinheaded’ or having a head ‘like a pea on a drum’? Well, if you have, and if you’re not quite broad-shouldered enough and don’t have the self-confidence to brush these awful words (and people) off, worry not.

Apparently, there is NO absolute correlation between size of head (the skull being a ‘case’ for the brain) and intelligence. As written in peer-reviewed scientific publications and reported by Fernández-Armesto (2015). To be frank, I was reading him for other reasons, but some guidance on anthropology and evolution is always handy, or heady. In this case.

You may or may not recall that in 2003, paleo-biologists/-anthropologists discovered the existence of a humanoid species they nicknamed “Hobbit man“, Homo floresiensis, on a dig in Indonesia. This species had a brain comparable in size to Chimpanzees – who are said to display the intelligence of 3- to 5-year-olds (actually not much more than our Shih-Tzu, but that’s beside the point). And yet, despite the relatively small brain size of Homo f., they possessed a toolkit very like our own ancestors – “Knowledgeable Man”, Homo sapiens – who had brains more than 3 times as large. We’re talking 40,000 years ago and so maybe this does not hold true today – or just maybe it does!

The amusing conclusion of this, from Fernández-Armesto’s point of view, is that Homo sapiens appears to be ‘overencumbered‘ with more brain than he/she/they need. This is problematic from a number of standpoints: big brains require a lot of energy for their upkeep, and they do not appear to deliver ‘proportional advantages‘. And, irrespective of whether they are evolutionary ‘aberrations’, since, as we know, evolution is not necessarily directed towards any sort of perfection or efficiency, the more brain you have the more can go ‘wrong’ with it. Fernández-Armesto speculates that larger brains could be the result, rather than the cause, of culture. If so, gawd help us. These theories ‘may help explain’ why, in general terms, evolution and extinction cycles have led to the disappearance of megafauna. But, alas, not the disappearance of big-headedness.

Remembering that a correlation indicates an association only and not a directly causative link.

Reference:

Fernández-Armesto, F. (2015) A Foot in the River: Why Our Lives Change and the Limits of Evolution. Oxford: OUP. ISBN: 978-0-19-874442-9

Felipe Fernández-Armesto is the William P. Reynolds Professor of Arts and Letters at the University of Notre Dame [2015]. His work has been recognized as pioneering across a very wide range of fields, including global history, environmental history, colonial history, maritime history, religious history, art history, the history of ideas, Mediterranean history, Spanish history, American history, the history of cartography, and the history of language. He has published numerous best-selling history books, including Civilizations, Millennium: A History of Our Last Thousand Years, 1492: The Year Our World Began, and Pathfinders: A Global History of Exploration, also published by OUP, which was awarded the World History Association Prize. [‘Herstory’, or even ‘Theirstory’ may be used instead – using Find and Replace]

Fernández-Armesto’s ideas on and interest in the evolution of brain size are shared by amongst others Robin Dunbar, a Professor of Evolutionary Biology at Oxford, who has theorised that larger brains ‘developed’ in Humans to cope with larger social groups, or at least were selected into the Human genome as those with larger brains are evidently thought to be able to cope with larger social groups than those with smaller brains. This appears to contradict Fernández-Armesto somewhat, yet there is a relevant current development in our workplace environment and in culture also, i.e. that we are tending to become more solitary (physically), as well as sedentary (the two are linked). And maybe eventually the sensory Homunculus that anatomy teachers may have shown their pupils/students in order to demonstrate the ‘brainpower’ given over to certain Human activities will also alter accordingly. Although the hand and, importantly, thumb size will obviously remain relatively large.

3 May 2024 – Dr Sophie Louisa Bennett, PhD Conservation Biology (Lincoln 2016), MA Modern & Medieval Languages – German and Swedish (KC 1987, Cantab 2020), Diploma in Translation – German into English (City University/Institute of Linguists 1998)

Took a look at historic voter turnout for elections for Police and Crime Commissioners this morning and found that, despite myself, I was impressed that as much as nearly 30% of the electorate bothered to turn out in Lincoln (although less than 20% in Lincolnshire as a whole) and similar results were recorded elsewhere nearby… Perhaps predictably.

Hurrah! Victory for democracy. What were the other 70% + doing? Talking about it on social media, on the streets of more-or-less dirty ‘old’ towns, in the shop and workplace… Why bother to vote, eh?

What have we now? Something I will name ‘de-mob-cracy’ because that is what it feels like to someone who will turn up and vote for a ‘supposed’ donkey – or even a dinosaur – if offered the opportunity. Plenty of opinions flying about, including about the people standing. Not ‘translated’ into correctly marked papers in boxes. (And they may even have been so desperate they counted the spoiled ones this time!)

I must admit to smiling when I pass by a house not far from home: the occupier has erected a sign stating that “Dinosaurs still rule the Earth“. Guaranteed to make every driver of a certain age smile as they drive over the level crossing. Yes, not merely walk the Earth, but drive around in their filthy petrol-driven backward-looking non-rechargeable non-hybrid high-emission cars, AND actually rule it too… There is something to be said for experience I suppose. But for how much longer?

Speaking of dinosaurs – that is exactly how someone of my generation described themselves in a greetings card not that long ago. Of my ‘generation’ of colleagues at a certain workplace there are only a few recognisable names remaining…

In the same card was a separate insert on which ‘Steve from graphics’ had written his name – at least I think it was that Steve – and with him, Jonathan S. Hmmm. Was this someone else I knew somewhat longer ago? And was there a musical connection? Cheeky rascally Steve, with the sort of naughty twinkle in his eye that all nice (and ‘narsty’) girls like – a dark-eyed darker-haired version of Adam Barlow on Coronation Street, without the Scottish accent, more like Joseph Fiennes come to think of it – who did something in his spare time that sounded vaguely filth. Something for the ‘young’ rather than dinosaurs like me. Although Steve is now nearly 20 years older than when I last worked with him and is probably by now a grime (or was it garage – still dirty in places), maybe drum and base impresario in his spare time!